Guest Post by Jakub Krzych, CEO and Co-Founder of Estimote

Jakub Krzych is CEO and Co-Founder of Estimote, Inc.

In this (epic) guest post, he provides his thoughts and insights into the future of Web and mobile apps, the introduction of Google Eddystone and beacon support, and his vision for what it takes to bring digital context to the real world.

Mobile & web apps and the future of beacon technologies

It’s been almost two years since Apple launched iBeacon, its own beacon format, and kicked off the contextual computing revolution. For the first time in computer history, a massively distributed and popular consumer device such as an iPhone was able to sense micro-location information broadcast by tiny, battery-powered radio devices.

The most important innovation was removing all of the friction in user interactions. Before iBeacon, it was possible to use QR codes and pass contextual information to the phone, but it was inconvenient: pulling out the phone, opening a QR code scanning app, focusing the camera on the code, etc. With beacon technologies, users just need to enter a beaconified location and a pre-programmed action will automatically appear on the screen—frictionless.

Apple made this technology elegant, privacy-oriented and straightforward. They anticipated billions of devices advertising their presence, thus they designed the iBeacon format to consist of 20 bytes containing a static identifier (UUID + Major + Minor)—enough to number all the objects on earth.

When a phone discovers the beacon and picks up the identifier, it triggers an app and the action assigned with that beacon. That is the most beautiful part of this elegant design: an app searching for a specific beacon is required. That means this technology is opt-in only. Apple knew that powerful and frictionless experiences might also put users at risk of being spammed or tracked without their knowledge. That’s why users have to explicitly opt in by simply downloading their favorite store or brand app. By doing that, they allow app creators to push notifications to their phone or to use location services.

When a user feels that the app shouldn’t use her location or that there’s not much value behind the app, she removes it. That is actually why many app developers concentrate on delivering amazing value to users.

If a user boards a train, arrives at the destination, and gets a notification with the ticket automatically charged to her credit card, that would be a magical experience. Or if she arrives at the airport and the app says exactly where to go and she is checked in by walking to the gate, that would be an amazing frictionless passenger experience.

However, it’s one thing to broadcast a static identifier and trigger hard-coded actions and another to engage with users through dynamic app content.

When a user walks into a furniture showroom and approaches the sofa she likes the most, she can see the picture, description, or price on her smartphone. But this data might change over time. In order to maintain it, developers might either hard-code all the new data into the app and push the new version to the App Store, or the app might simply fetch the data from the server by passing beacon identifiers to CMS solutions, where marketers could keep the content up-to-date.

Eddystone by Google and the mobile web

But what if we want to interact with many brands and many airports or retail stores? Do we need to download all these apps? Not really.

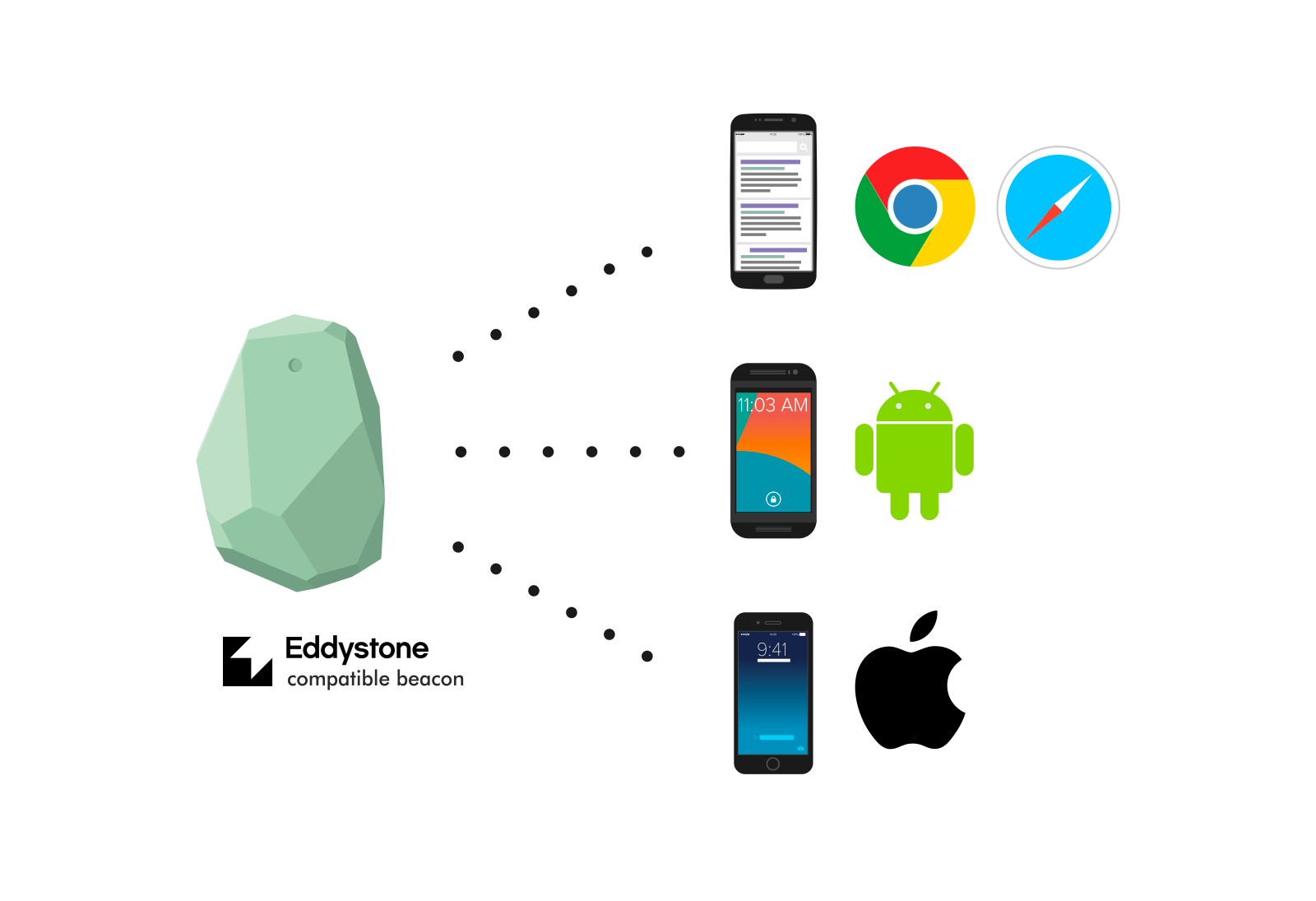

Google recently released a different beacon format called “Eddystone.” Unlike iBeacon, it doesn’t broadcast only an identifier, but also a pre-programmed website URL. So instead of having many different apps fetching contextual data, we might have just one, and it can simply be the web browser.

A similar shift happened in the early ‘90s. There were many standalone apps exchanging data with servers using different data formats. There was, for example, the FTP protocol and the FTP client app, IRC and its client, Usenet, Gopher, Mail, etc. Over time, most of these services moved to the web and were consumed by the internet browser, which could run on any computer, any processor architecture, and any screen.

It was faster and cheaper for developers to design, build, distribute, and update web apps. Broadband and modern browsers made it impossible for users to distinguish the so-called Web 2.0 apps such as Gmail, Google Maps, and Google Docs from their standalone competitors like Outlook or Excel.

That trend is not visible in the mobile world yet. Most of the popular services such as Snapchat, Facebook, or games still run as standalone native apps. It’s because of performance: native apps can run much faster, they optimize battery consumption, and they have access to low-level peripherals such as built-in sensors, cameras, memory, etc.

Over time, the defragmentation of mobile devices, platforms, and screen sizes might again result in a shift towards web apps, especially if browsers become faster and gain more access to low-level peripherals. Google, for example, recently released a Chrome browser for iOS that can natively scan for URLs broadcast by beacons. This might become the promise of a single app talking to many beacons.

Web app or native mobile

One app installed on the phone and responding to all beacons might be an elegant solution to the app distribution problem.

Nevertheless, the most progressive brands and retailers, with their innovative mobile teams, will keep investing in their own loyalty or in-store-experience apps. They know that the only way to have full control over the data, branding, and end-to-end user experience is via standalone apps installed on consumer devices.

They also know that the only way to convince users to download these native apps is to provide them with amazing value. Beacons help with that, by removing the friction and making apps smarter.

UI and UX designers can leverage beacons to understand the microlocation or context of their users. Also, by using additional data from sensors, such as motion or temperature, user interfaces can be simplified or sometimes completely reduced.

Beaconified apps help their users focus on the main goals behind the apps and can impact important metrics such as engagement, usage, or retention.

Scaling beacon deployments

The typical app beaconification process starts with experimentation and prototyping. A proof-of-concept app is created with just a few beacon dev kits. Pitched internally, it can often attract attention from product people and decision-makers. Once an app is budgeted and the mobile team allocated, the proper app development process starts. After few weeks or months of app development, beacons are deployed to the production environment.

For airports, shopping malls, or huge retailers beaconifying enormous spaces and thousands of locations, deployment might be a logistics nightmare. They will most likely optimize for the simplicity of the installation and maintenance as well as the cost of that operation. It’s easy to calculate that a workday of deployment crew to complete the installation, configuration, and testing, multiplied by thousands of stores, can result in multimillion-dollar bill.

That is the main reason it’s unlikely that large beacon deployments will install beacons that require power cords, manual configuration, and floor-plan assignments. Even tiny details such as the lack of a built-in adhesive layer can impact the efficiency of the deployment.

On batteries and hardware upgrades

For the same reasons, it is unlikely that retailers will replace batteries in their beacons. The cost of that operation would be higher than installing new ones.

Once installed, beacons should last long enough that they can be replaced with the new generation: technology cycles in that industry move fast. Last year, Bluetooth SIG released two updates of their BLE standard and one of them requires completely new hardware for both the beacon and the mobile phone. So three-year-old beacons will be obsolete anyway.

However, software or hardware upgrades shouldn’t affect applications running on top of this infrastructure. The most progressive beacon companies will not only optimize the cost of deployment but also the simplicity of the migration.

For all of these reasons, it’s clear that retailers won’t install multiple beacons broadcasting exclusive data formats for different mobile platforms or apps. We shouldn’t expect that there will be beacons only for Microsoft, Google, or Facebook. It just won’t happen.

There’s nothing preventing beacons from broadcasting as many packets as we want. They’re just tiny computers, after all.. These packets can also consist of whatever data we want. That’s why any customer who purchased Estimote Beacons in the past can simply update them over the air and turn on an Eddystone packet or switch to iBeacon at any time. No new hardware is required. At Estimote, we are committed to supporting whatever the popular future beacon format is.

We expect rapid development of beacon technologies, new formats, sensor integrations, and security updates. That is why we advise our customers to choose a beacon partner wisely and to make sure purchased beacons can be frequently and effortlessly updated with new firmware.

Remote fleet management

An elegant and easy fleet management technique including firmware updates isn’t a huge challenge. Each and every beacon is a tiny computer and can connect to phones or other beacons. It can also exchange configuration data, including firmware.

That is why at Estimote we do not have additional devices or hubs to configure or upgrade our beacons. All the beacons can be upgraded over the air, and we use technology already built-in to the phones. When users visit different locations and their apps interact with beacons, they can simply connect and update beacon configuration or firmware in the background: it’s just a few kilobytes, so there is no impact on usage. And it’s 100% secure and respects the user’s privacy—no personal data are collected or transferred.

Because of the operation cost argument mentioned before, there’s no point in installing additional hardware to remotely manage beacons. Whenever beacons are installed, users with compatible apps should be in the proximity. After all, if there are no users around, why are beacons there?

On security and risks

Part of the fleet management routine should also be security updates. Many retailers or airports investing in beacon infrastructures are very sensitive to any potential vulnerabilities of beacon networks.

We can easily imagine airport passengers receiving notifications about cheaper flights to the same destination from a competitor airline exactly when they check in at the gate. Or, consumers visiting retail stores might receive coupons from E-commerce apps detecting their location in specific departments, causing a showrooming effect.

All of this could happen if competing apps sense the presence of beacons and remember their static identifiers. Since beacons are tiny computers, they can dynamically compute these identifiers so that only authenticated apps could decode them. This is exactly how we implemented Secure UUID mode. Our customers who want to protect their networks can simply turn on Secure UUID, and competing apps won’t be able to easily resolve the location.

Of course, every computer technology is hackable. But even if that happened, the risk is still very low, because there’s an additional layer of security: the Apple App Store approval process. Apple would never agree to publish in the App Store software malware that would basically have access to information it shouldn’t. These days, App Stores are the main distribution channels for apps, so respected app creators won’t risk dealing with Apple on that front.

Infrastructure sharing and innovation acceleration

Once the network of beacons is built and secured, there might also be opportunities to share it with other app creators. That is why we built a feature we call “beacon infrastructure sharing” on top of our cloud and beacons. Our customers can allow any app to take an advantage of the infrastructure and the context established in the venue.

We see retailers enabling different brands to use beacon infrastructure so their apps might trigger notifications when customers visit a partner retail environment. The same with airports, which might share different terminals or gates with different airline or duty-free apps.

We should expect that in the future, locations that are attractive and offer value to visiting consumers will sell access to their beacon infrastructures, via exactly the same model we’ve seen on the web with popular websites and ads. If someone creates a website with high traffic, they can make part of that website available for banners, cookies, or widgets as long as those components don’t confuse users. Otherwise, that website would lose them quickly.

With the security component and infrastructure sharing, any beacon network owner can invite third-party apps and offer campaigns for a specific period of time. For exactly the same reason that the visual language of layouts and banners have been used on the web by agencies and web owners, there must be similar visual language to manage campaigns and interactions in physical venues. That language has been already created: it’s called “floor plans and maps” and has been used by retailers, airports, museums, and their suppliers for years.

Indoor location with beacons

Being able to quickly deploy hundreds of beacons and see them immediately on a floor plan has been always a long-term goal for Estimote. Every day we get closer to that vision because of our heavy investment in beacon-based indoor location.

We’ve built an amazing data science team that has created robust indoor location algorithms and SDKs that anyone can build into their apps to achieve an accuracy of locating people and their phones inside a building to within just a few meters.

In order to make this extremely simple, we invented an auto-mapping tool. Even if the deployment crew doesn’t have a floor plan, they can map the space automatically using our Indoor Location App from the App Store. They just need to walk around the room once. The mapped space and beacon locations are automatically saved in the cloud, where they can be edited, managed, or shared with third-party apps.

There is also an analytics component venue owners can use to better understand the behavior of their users in their locations. The RESTful API makes it extremely simple for integrations or deeper insights.

The privacy issue here is solved by the same opt-in mechanism explained before. If users are offered strong value such as wayfinding, asset tracking, etc., they will download an app with a built-in Indoor Location SDK and explicitly agree to be located.

Knowing the exact location of people and being able to resolve their context is one thing, but having more insight into their interaction with the objects around them is another. Both of these components can help to design amazing context-aware mobile apps and experiences. That is why at Estimote we have also invested heavily in sensors built into beacons and invented “nearables.”

Using tiny beacons in the form factor of stickers, users can turn ordinary things into smart, connected objects. These objects can broadcast into the air not only their presence, but additional metadata such as temperature, motion, orientation, and state duration. This is all possible because of our very own connectionless Nearable Packet, which we introduced last year long before Google started to work on Eddystone.

Apps for the physical world

If you combine all of this—beacon infrastructure sharing, easy-to-use, and precise indoor location, plus nearables—you will very quickly understand where this is going. Finally, all these components make it possible to build real apps on top of physical locations that are full of objects. It’s a tremendous shift from apps designed for phones to apps designed for airports, retails stores, or museums.

For example, Estimote apps designed for one museum can be “run” on top of any museum that is “compatible.” A scavenger app built for one retail store can be scaled to thousands of stores. That is the long-term vision behind beacon technologies: to make it extremely simple to develop, configure, deploy, and distribute apps for physical locations.

At Estimote, we have been executing that vision since the day we launched this project. We interact with many pioneers in the community, and we are very proud of their help in making this technology better every day.

We are extremely excited that all the major players, including Apple and Google, are fully on board with beacons, and we look forward to seeing what comes next and how contextual technologies will evolve. The most exciting part is the fact this is still at an early stage, with many innovations and pioneer inventions ahead.

Share Your Thoughts

Join our e-mail list for more on iBeacons and BLE. Join the conversation on Twitter, or connect with me on LinkedIn.

Come on – let’s give a shout-out to Jakub. Epic post – and lots to think about. What do you think he gets right (or wrong) about the future of mobile and web apps in the era of Eddystone and iBeacon?